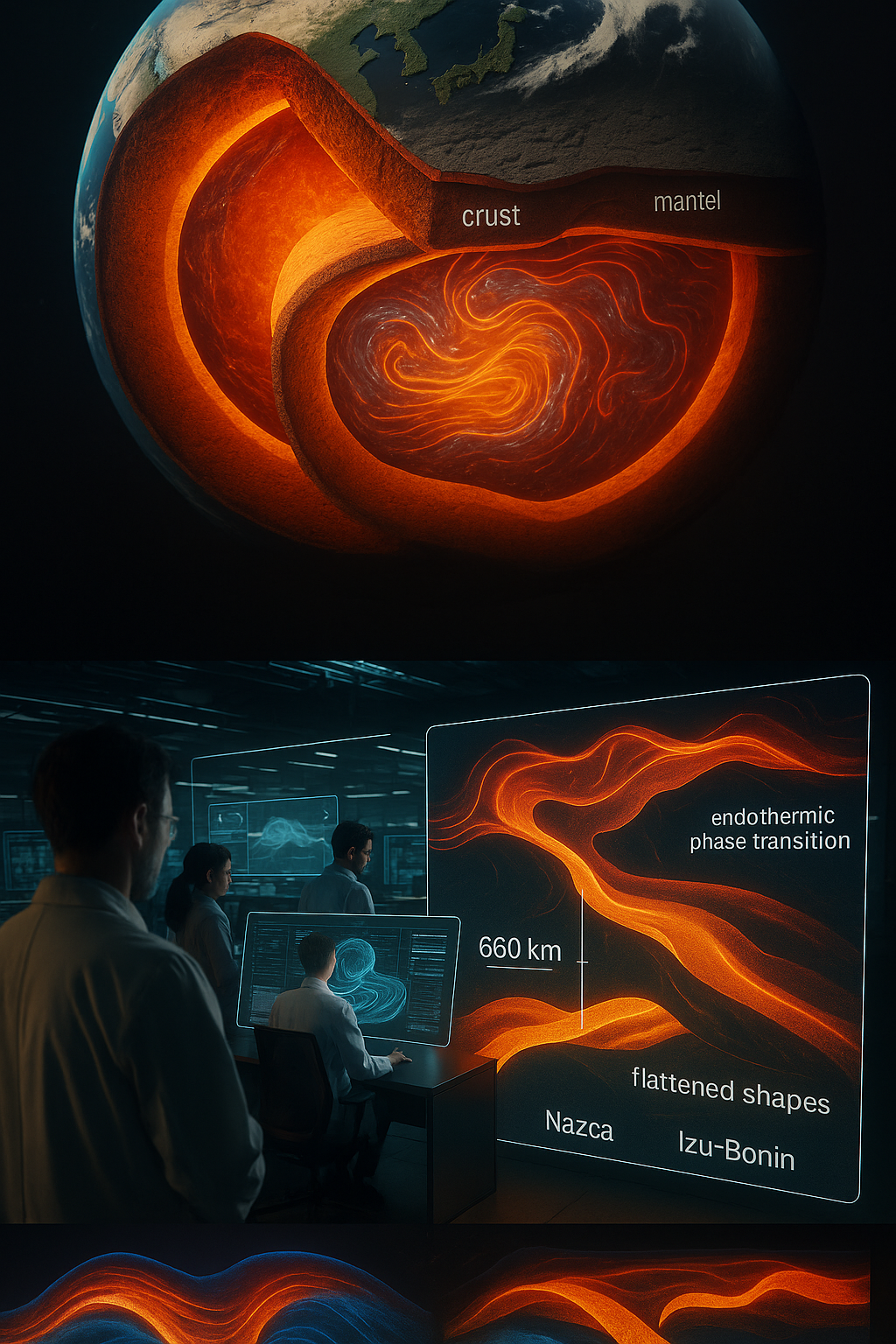

For decades, geologists have wondered why some slabs of Earth’s ancient ocean floor dive deep into the planet’s mantle, while others appear to flatten and stall hundreds of kilometers below the surface. Now, a powerful new supercomputer study may finally hold the answer.

The Power of Modeling

An international team of scientists from the University of Glasgow, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the International Space Science Institute (Switzerland) has harnessed the UK’s ARCHER supercomputer to simulate how giant slabs of oceanic crust behave as they sink into Earth’s interior — a process known as subduction.

Their research, published in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, explores how the interaction between Earth’s surface plates and the mantle’s viscosity (its internal resistance to flow) determines whether subducted slabs continue sinking or flatten out at depth.

What Happens Deep Below

Approximately 660 kilometers beneath our feet lies a crucial boundary within the Earth’s mantle, known as the endothermic phase transition. Here, certain minerals resist further sinking, and the mantle itself becomes stiffer between 660–1,000 km. This barrier can stop the slabs from descending — but not always.

Dr. Antoniette Greta Grima, the study’s lead author from the University of Glasgow’s School of Geographical & Earth Sciences, explains that the overlying plate — whether continental or oceanic — plays a decisive role in the fate of these subducting slabs.

Continental vs. Oceanic Plates

-

When a thick continental plate sits above a subduction zone, and the mantle stiffens at around 1,000 km, slabs bend sharply at 660 km before continuing downward — forming a “stepped” shape, like a flight of stairs.

-

When a thin oceanic plate lies on top, slabs tend to flatten at 660 km, unable to overcome the resistance below.

This finding shows that continents not only shape the landscapes we see on the surface — they also influence the dynamics of the planet’s internal “engine.”

The “Slab Bending Ratio”

Dr. Grima introduced a new metric called the slab bending ratio, which quantifies how subducting plates deform. This measure helps predict whether a slab will stall or sink deeper toward the core–mantle boundary.

The simulations match real-world data:

-

The Nazca slab beneath Peru dives steeply, showing a stepped pattern typical of continental influence.

-

The Izu-Bonin slab near Japan flattens — exactly what’s expected when one oceanic plate subducts beneath another.

A Deeper Connection Between Surface and Interior

Dr. Grima compares their approach to medical imaging:

“Just as doctors use X-rays or CT scans to look inside the human body, geologists use seismic tomography to image the Earth’s interior. Our models don’t just reproduce what we see — they explain it.”

Her team’s results reveal a powerful connection between what happens on the surface and what occurs thousands of kilometers below. Where continents exist, their mass and rigidity help drive slabs deeper, influencing the global flow of Earth’s mantle and, in turn, the distribution of earthquakes and volcanic activity.

Why It Matters

Understanding how subducted slabs behave helps scientists:

-

Predict regions more prone to major earthquakes and volcanic eruptions,

-

Improve models of Earth’s internal convection, and

-

Reveal how plate tectonics has shaped our planet over geological time.

Supercomputing power is giving us an unprecedented look at how Earth’s “hidden engine” works — connecting the continents we live on to the deep forces that move the planet from within.

Source: Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems (2025) — DOI: 10.1029/2025gc012593

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.