A Celestial Dreamscape in Scorpius

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has once again stunned astronomers and the public alike. In its latest release, the telescope captured an image of Pismis 24, a young star cluster embedded within the Lobster Nebula — a cosmic nursery located about 5,500 light-years away in the constellation Scorpius.

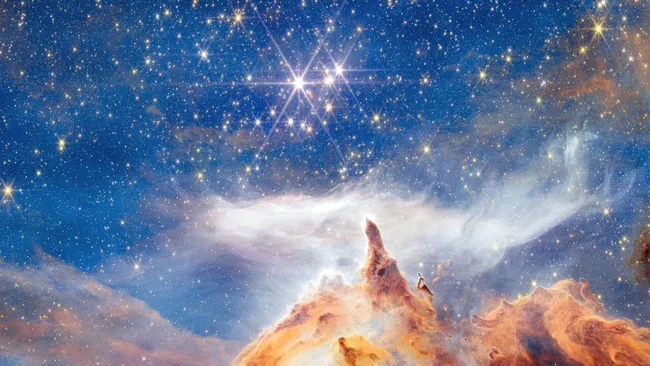

In the dazzling scene, bright stars pierce through towering peaks of orange and brown dust, resembling a craggy mountain range lit by starlight. The tallest of these spires — a pillar of gas and dust at the image’s center — stretches 5.4 light-years from base to tip, equivalent to about 200 solar systems placed side by side out to Neptune’s orbit.

This surreal vista, captured in infrared by JWST’s Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam), is a living portrait of stellar creation and destruction — where radiation from massive newborn stars both erodes and nurtures the clouds that gave birth to them.

Where Stars Are Born and Die Young

Pismis 24 is a self-sustaining stellar nursery, one of the closest and most active star-forming regions in our galaxy. Within its glowing pillars, intense ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from young, massive stars carve out new cavities while triggering further waves of star formation.

Among these giants is Pismis 24-1, once believed to be a single star weighing an impossible 200–300 solar masses — nearly double the theoretical upper mass limit for stars. However, in 2006, observations by the Hubble Space Telescope revealed it to be at least two distinct stars, each weighing roughly 74 and 66 times the mass of our Sun.

Even so, the pair remains among the most luminous and powerful stars in the Milky Way, producing radiation intense enough to sculpt the nebula’s intricate “starlit mountaintops” that JWST now reveals with unmatched clarity.

Decoding the Cosmic Palette

Like all JWST images, this one’s ethereal beauty is also a scientific map of wavelengths. Each color corresponds to a specific element or temperature:

-

Cyan: hot, ionized hydrogen gas

-

Orange: warm interstellar dust

-

Deep red: cooler, denser hydrogen regions

-

White: starlight scattered through dust

-

Black: dense clouds that even JWST’s infrared eyes cannot penetrate

Together, these tones form a visual symphony of matter, energy, and light — revealing how stars shape and reshape the universe around them.

A Stellar Legacy in the Making

This “starlit mountaintop” image not only stands as one of JWST’s most awe-inspiring portraits to date but also deepens our understanding of massive star formation and the turbulent environments where galaxies forge their brightest beacons.

Every structure in the image — every ridge, plume, and filament — tells the story of energy sculpting matter across cosmic time.

“It’s a window into the cosmic feedback loop,” wrote the European Space Agency in its image release. “As young stars sculpt their birth clouds, they create the next generation of stellar nurseries — a self-sustaining process that keeps our galaxy alive.”

Acknowledgements

This article draws upon data and imagery provided by:

- Jamie Carter

Edited by Sadie Harley, reviewed by Robert Egan -

NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), under the operation of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI).

-

A. Pagan (STScI), for image composition and color calibration of JWST’s Pismis 24 observation.

-

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) legacy archives for complementary data on stellar mass and dynamics.

-

The European Space Agency’s media and outreach division, for descriptive and interpretive content related to JWST’s infrared imaging.

-

DatalytIQs Academy, for its ongoing efforts in space education, data-driven astronomy, and public science engagement — translating cutting-edge astrophysical research into accessible multimedia learning for global students, enthusiasts, and educators.

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, and A. Pagan (STScI)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.