Astronomers capture the first-ever radio image of two supermassive black holes in orbit, confirming a theory 40 years in the making.

For the first time in human history, astronomers have captured an image showing two black holes orbiting each other. The extraordinary discovery was made in the quasar OJ287, a celestial object so bright that even amateur astronomers can detect it from Earth.

This achievement, led by an international team of researchers from the University of Turku (Finland) and collaborators using the RadioAstron satellite, provides the strongest evidence yet that binary black holes — pairs of massive black holes locked in a gravitational dance — really do exist.

A Quasar with a Mystery

Quasars are the intensely luminous cores of galaxies, powered by supermassive black holes feeding on surrounding gas and dust.

OJ287, located about 5 billion light-years away, has long puzzled astronomers. Since the early 1980s, it has exhibited a recurring 12-year cycle of brightness changes, indicating that something extraordinary is occurring at its core.

In 1982, Finnish astronomer Aimo Sillanpää proposed a daring explanation: OJ287 might not have one black hole, but two, orbiting each other in a 12-year cycle. His idea sparked decades of observation and mathematical modeling.

From Theory to Image

Fast forward to the 2020s — after years of calculations and light-curve monitoring, Doctoral Researcher Lankeswar Dey and his team successfully modeled the orbits of OJ287’s suspected black holes. What remained was the most challenging question: Could both black holes actually be seen?

The answer arrived through radio astronomy. Visible-light telescopes, such as NASA’s TESS satellite, detected light from both black holes, but the images appeared as a single unresolved point. To separate them, scientists needed 100,000 times higher resolution — achievable only through radio telescopes operating in space.

Enter RadioAstron, a Russian-led satellite observatory with an antenna extending halfway to the Moon. Its immense distance from Earth created a vast virtual telescope, capable of resolving the finest cosmic details. When OJ287 was observed using this system, two distinct bright spots appeared — one for each black hole.

The Historic Image

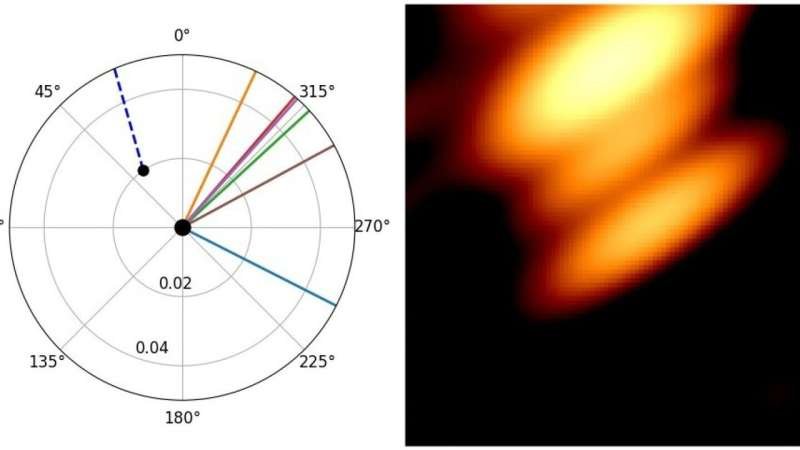

The final composite shows two key components:

-

Left Panel: A theoretical diagram by Lankeswar Dey, predicting the positions and jet directions of both black holes.

-

Right Panel: The radio image captured by RadioAstron (J.L. Gómez et al., 2022), clearly revealing two bright points corresponding to the two black holes, along with the jet emitted by the smaller one.

The alignment between theory and observation confirmed what astronomers had hoped for decades: binary black holes are real.

“For the first time, we managed to get an image of two black holes circling each other,”

— Professor Mauri Valtonen, University of Turku.

A Twisting Jet — The “Wagging Tail”

In a surprising twist (literally), researchers also identified a new type of black-hole jet — a twisted stream of particles emanating from the smaller black hole. Because it rapidly orbits its larger companion, the jet appears to wobble and swing like the end of a garden hose.

This “wagging tail” motion could change direction as the orbit evolves, providing a rare opportunity to observe relativistic effects in real time.

This image is more than just a cosmic snapshot — it’s a window into the evolution of galaxies and the nature of gravity itself.

-

🪐 Binary black holes are believed to form during galactic mergers, when two supermassive black holes sink toward the center of the new galaxy and begin orbiting one another.

-

🔊 Their eventual collision is expected to produce powerful gravitational waves, ripples in space-time first predicted by Einstein.

-

🔭 Understanding these systems helps astronomers refine models of black-hole growth, galaxy formation, and jet-driven feedback that shapes interstellar environments.

The work also demonstrates the power of global radio astronomy networks and space-based telescopes working in unison — a model for future missions like the next-generation Event Horizon Telescope and LISA gravitational wave observatory.

Reference

Dey, L., Valtonen, M., Sillanpää, A., Gómez, J.L., et al. (2025).

Imaging Two Orbiting Black Holes in Quasar OJ287.

Published in The Astrophysical Journal.

DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2510.06744

The Beginning of a New Era

The image of OJ287’s twin black holes is more than a technical triumph — it’s a glimpse into the violent yet elegant choreography of the universe.

Two invisible giants, circling each other in the darkness, sending out signals across billions of light-years — and now, for the first time, we can finally see them.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.