The Birth of a Crystal That Ticks in Time

Crystals are among nature’s most orderly creations — glittering solids whose atoms form repeating patterns in space. But what if matter could also form a repeating pattern in time?

This is the strange reality of time crystals, a phase of matter first proposed by Nobel Laureate Frank Wilczek (2012). Unlike ordinary crystals, which repeat in space, time crystals repeat their motion endlessly in time, even in their lowest-energy (ground) state — a kind of perpetual motion permitted only by quantum mechanics.

Time crystals were first observed experimentally in 2016. Now, in a major leap forward, physicists at Aalto University’s Department of Applied Physics (Finland) have connected a time crystal to another system external to itself — an achievement that could pave the way for ultra-stable quantum computers and precision sensors.

The work, led by Academy Research Fellow Dr. Jere Mäkinen, is published in Nature Communications.

Linking a Time Crystal to the Outside World

In the quantum world, perpetual motion is possible only if the system remains isolated. Any external interference — even an observation — normally collapses the delicate cycle.

“A time crystal had never before been connected to any external system,” explains Dr. Mäkinen. “But we did just that and showed, also for the first time, that you can adjust the crystal’s properties using this method.”

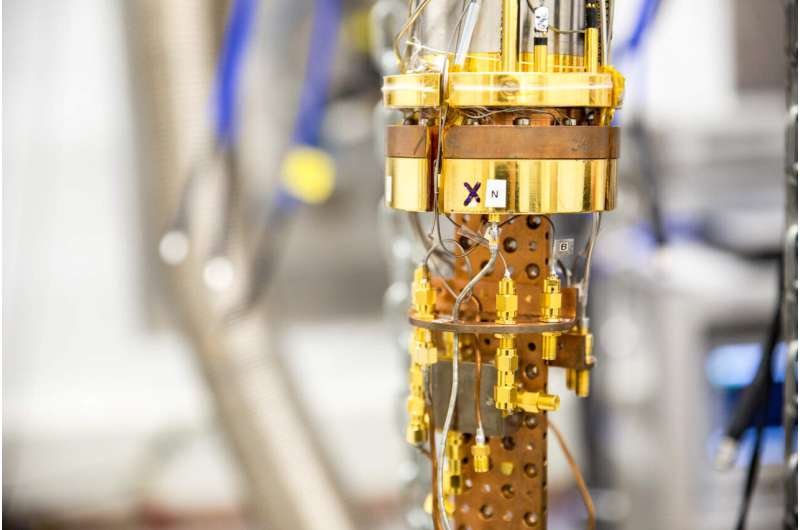

The team created their time crystal by injecting radio-frequency energy into a superfluid made of helium-3, cooled to near absolute zero. The radio waves pumped magnons — quasiparticles that behave like individual particles — into the fluid.

When the external pump was turned off, the magnons spontaneously organized into a time crystal that kept oscillating for over 108 cycles, lasting several minutes before fading beyond detection — an unprecedented lifetime for any such quantum system.

Quantum Harmony: A Crystal Meets a Mechanical Oscillator

During this fading period, the time crystal began interacting with a nearby mechanical oscillator — effectively forming an optomechanical system, where vibrations in the crystal coupled with the motion of the oscillator.

“We showed that changes in the crystal’s frequency mirror the optomechanical phenomena seen elsewhere in physics — the same principles used to detect gravitational waves at the LIGO observatory,” says Mäkinen.

By reducing energy loss and tuning frequency, the Aalto team’s setup could one day reach the boundary of the quantum mechanical limit, where time-based oscillations can be precisely controlled for computing and sensing applications.

Toward Quantum Memory and Precision Sensing

The implications are profound. Time crystals last far longer than typical quantum systems, which tend to lose coherence rapidly. This longevity could make them ideal memory components for future quantum computers — capable of maintaining information for extended periods with minimal energy loss.

They could also serve as frequency combs or reference oscillators in high-sensitivity measurement systems, improving the precision of atomic clocks, gravitational-wave detectors, and navigation technologies.

“The best-case scenario is that time crystals could power the memory systems of quantum computers to significantly improve them,” says Mäkinen. “They could also function as frequency references for ultra-sensitive measurement devices.”

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge:

-

Aalto University’s Department of Applied Physics and the Academy of Finland for research funding and laboratory support.

-

Dr. Jere Mäkinen, Prof. Vladimir Eltsov, and the Low Temperature Laboratory team for their pioneering work in quantum fluid dynamics.

-

Nature Communications for the publication and scientific dissemination of the study.

-

The foundational theoretical insights of Prof. Frank Wilczek, whose proposal of time crystals in 2012 inspired this line of research.

-

DatalytIQs Academy, for its contribution to science communication, quantum education, and interdisciplinary public engagement, translates frontier research in quantum materials and computing into accessible learning experiences for students, professionals, and innovators worldwide.

Special thanks to Mikko Raskinen (Aalto University) for the striking visualization of the time crystal formed atop a superfluid under ultracold conditions.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.