New experiments reveal how chemical balances in ancient oceans delayed and then accelerated the planet’s Great Oxidation Event.

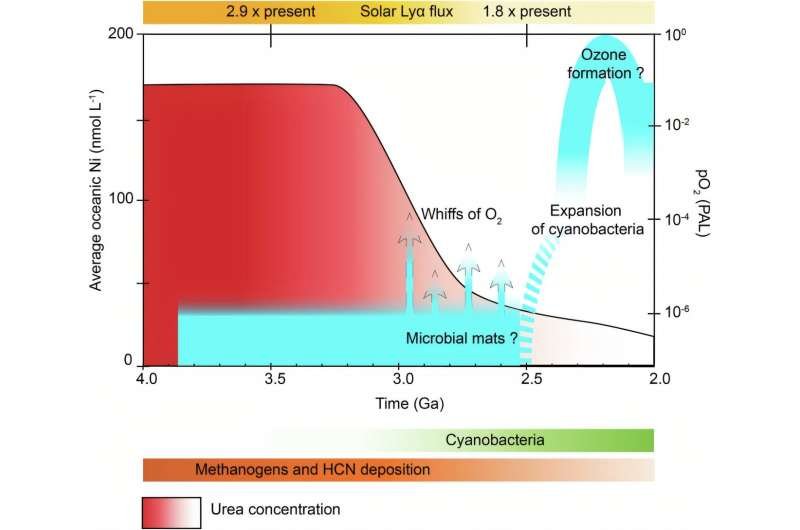

Roughly 2.4 billion years ago, Earth experienced one of the most transformative moments in its history — the Great Oxidation Event (GOE). This was when the planet’s atmosphere first became rich in oxygen, allowing complex life to eventually evolve.

But for hundreds of millions of years before that, oxygen-producing microbes known as cyanobacteria already existed. So why did it take so long for oxygen to accumulate in the atmosphere?

A new study from Okayama University offers a surprising answer: the key may lie in two small but powerful molecules — nickel and urea — that once filled the early oceans.

The Mystery of Earth’s Delayed Oxygenation

Scientists have long known that oxygenic photosynthesis — the process by which cyanobacteria split water molecules to release oxygen — evolved well before the GOE. However, despite this biological innovation, the planet’s atmosphere stayed almost oxygen-free for hundreds of millions of years.

Previous theories blamed volcanic gases, iron oxidation, or methane-dominated atmospheres for absorbing oxygen as fast as it was produced. But a complete explanation remained elusive — until now.

“We wanted to understand how a tiny microbe was capable of changing an entire planet,”

said Dr. Dilan M. Ratnayake, the study’s lead author, from the Institute for Planetary Materials, Okayama University (now at the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka).

“Understanding this mechanism could even help us figure out how to generate oxygen on other planets.”

Recreating the Archean Earth

To solve the puzzle, Dr. Ratnayake’s team ran a two-stage experimental simulation of Archean Earth, a period between 4 and 2.5 billion years ago, when life was mostly microbial and the atmosphere lacked oxygen.

Step 1: Could urea form naturally?

In the first experiment, the researchers mixed ammonium, cyanide, and iron compounds, then exposed them to ultraviolet (UV-C) radiation — the type of light that would have reached the surface before the ozone layer existed.

The results showed that urea, a vital nitrogen-rich molecule, could form abiotically under these ancient conditions. This finding suggests that urea — long considered a product of life — may have been present before life fully evolved, serving as a nutrient source for primitive organisms.

Step 2: How did urea and nickel affect cyanobacteria?

In the second experiment, cultures of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002, a modern cyanobacterium, was grown under light–dark cycles with varying levels of urea and nickel.

By tracking optical density and chlorophyll a levels, the researchers measured how these compounds affected microbial growth.

The Nickel–Urea Bottleneck

The findings revealed an elegant chemical interplay. In the early oceans, both nickel and urea were abundant. Nickel, though essential for enzymes that help cyanobacteria process nitrogen, can be toxic in excess. Similarly, while urea provides vital nitrogen, high concentrations inhibit growth.

This created a metabolic bottleneck — conditions that allowed cyanobacteria to exist but prevented them from thriving enough to alter atmospheric chemistry.

As time passed, nickel levels declined due to geological changes, and urea concentrations stabilized, creating the perfect balance for massive cyanobacterial blooms. These blooms finally pumped enough oxygen into the atmosphere to trigger the Great Oxidation Event.

“Nickel and urea had a complex yet fascinating relationship,”

Dr. Ratnayake explained.

“At lower concentrations, they promoted the proliferation of cyanobacteria, setting off the chain reaction that ultimately oxygenated Earth.”

A Blueprint for Life — on Earth and Beyond

The study’s implications go far beyond early Earth. Understanding how small chemical changes shaped the oxygen balance provides a new framework for detecting life elsewhere in the universe.

“If we can clearly understand the mechanisms that increase atmospheric oxygen, it will guide how we search for biosignatures on other planets,”

said Ratnayake.

Future missions, including Mars Sample Return and exoplanet biosignature studies, could use these insights to identify worlds where trace compounds like nickel and urea may drive — or limit — the emergence of life.

Rethinking Earth’s Evolutionary Timeline

By experimentally confirming that urea could form under prebiotic conditions and showing how its interaction with nickel influenced microbial ecosystems, the research provides a new geochemical perspective on how life transformed our planet.

In essence, Earth’s oxygen boom wasn’t just about biology — it was a delicate chemical balancing act. The gradual decline of nickel and the moderation of urea created the ecological window for cyanobacteria to flourish, reshaping the atmosphere and paving the way for all oxygen-dependent life that followed.

Reference

Ratnayake, D. M., Tanaka, R., & Nakamura, E. (2025).

Nickel and urea controls on cyanobacterial proliferation and the timing of Earth’s oxygenation.

Communications Earth & Environment (Nature Portfolio).

DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02576-8

Credit: Okayama University / Communications Earth & Environment (2025).

A Delicate Chemical Symphony

This study elegantly connects chemistry, biology, and planetary evolution into one narrative. The interplay of nickel, urea, and sunlight not only determined when Earth became breathable but also offers clues about how to make other worlds livable.

As we continue searching the cosmos, understanding Earth’s own oxygen story reminds us that life depends not just on the presence of water or light — but on the right balance of elements at the right time.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.