Discovery of Binary Stars Marks First Step Toward a “Movie of the Universe”

By The Australian National University (ANU)

Edited by Gaby Clark • Reviewed by Robert Egan

Educational commentary by DatalytIQs Academy

A Galactic Film in the Making

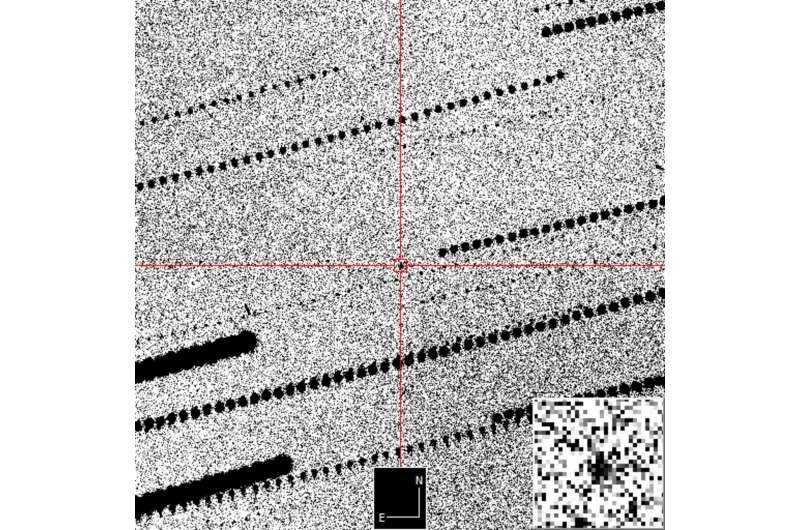

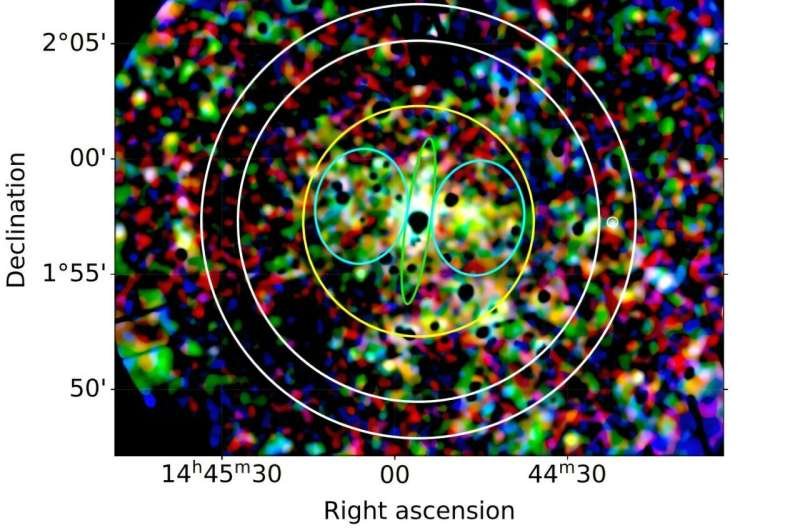

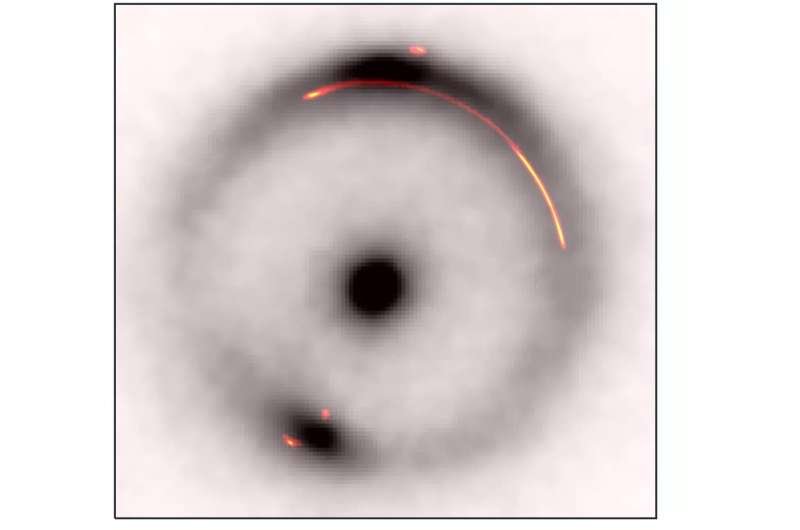

Astronomers from The Australian National University (ANU) have made a discovery that could reshape our understanding of how galaxies—and perhaps the universe itself—evolve. Using the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, researchers detected binary stars within the outer reaches of the globular cluster 47 Tucanae, one of the oldest and brightest star systems in the Milky Way.

The finding, part of the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), marks the beginning of an ambitious 10-year quest to create a “movie of the universe” — capturing billions of stars and galaxies as they move and transform across time.

Binary Stars: Cosmic Duos that Shape the Galaxy

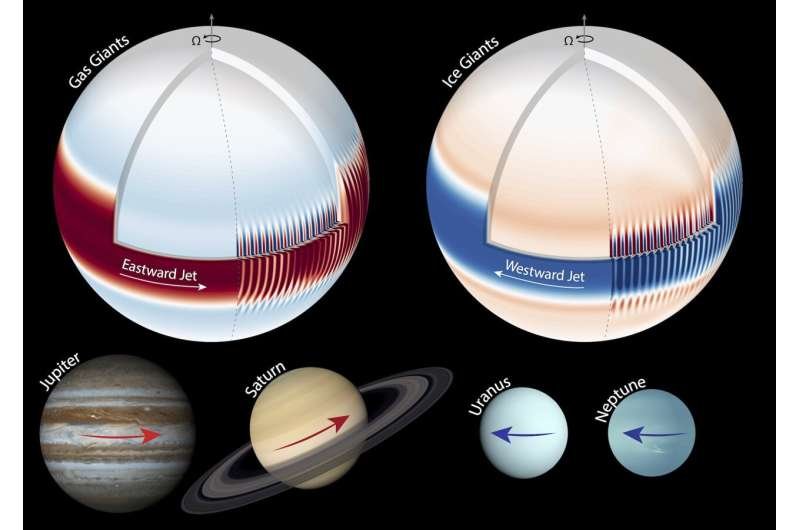

Binary stars—two stars orbiting a shared center of gravity—are the hidden engines of stellar evolution. Within dense globular clusters, they:

-

Exchange energy with neighboring stars,

-

Influence whether a cluster remains stable over billions of years, and

-

Give rise to exotic celestial objects like blue stragglers — unusually luminous stars that seem younger than their surroundings.

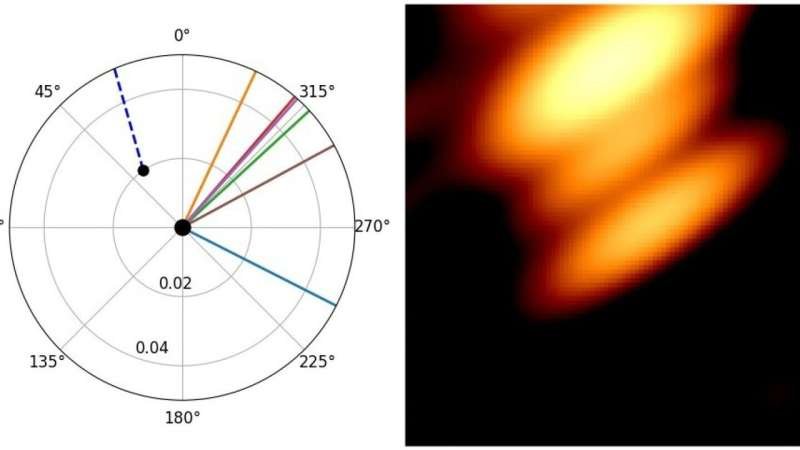

Using Rubin’s first public dataset (Data Preview 1), ANU scientists detected binaries in 47 Tucanae’s outer regions for the first time. Surprisingly, they found that binary stars are three times more common in the outskirts than in the crowded central zones previously explored by the Hubble Space Telescope.

This suggests that while dense centers may destroy or disrupt binary systems through frequent stellar interactions, those in the calmer outskirts survive intact — preserving a glimpse into the cluster’s original stellar makeup.

Unveiling 47 Tucanae: A Stellar Time Capsule

“47 Tucanae has been studied for over a century,” said Professor Luca Casagrande of ANU,

“but only now, thanks to Rubin, can we truly map its outskirts and uncover how these ancient clusters assembled.”

The cluster—visible to the naked eye from the Southern Hemisphere—contains hundreds of thousands of stars tightly packed within a few dozen light-years. These ancient stellar cities serve as natural laboratories for studying the long-term evolution of stars and galaxies.

The Rubin Observatory’s LSST will allow astronomers to monitor these systems repeatedly, building a frame-by-frame record of cosmic changes.

The result will be nothing less than a dynamic, evolving portrait of the universe — a scientific “film reel” documenting how matter and motion shape galaxies over time.

A Transformative Tool for Astronomy

Even at its early stage, Rubin’s LSST has demonstrated its revolutionary potential.

“Even in its first test data, LSST is already opening a new window on stellar populations and dynamics,”

said Professor Helmut Jerjen, co-author of the study.

Over the next decade, the observatory will map billions of binary systems across the entire southern sky, providing the most complete census of stars ever achieved and testing models of cluster and galaxy formation with unprecedented precision.

DatalytIQs Academy Perspective: Learning from the Cosmos

At DatalytIQs Academy, we celebrate discoveries like this as perfect examples of how astronomy, data science, and physics converge.

This study highlights:

-

The importance of long-term observation and time-series analysis in understanding cosmic evolution.

-

The power of big data in astronomy — Rubin’s LSST will generate tens of petabytes of data, demanding advanced analytics, machine learning, and visualization tools.

-

The value of binary systems as astrophysical “testbeds” for energy transfer, stellar dynamics, and galactic history.

Our learners explore these same analytical principles in courses on Astrophysical Data Analytics, Simulation Modeling, and Machine Learning for Space Science, connecting classroom theory to frontier discoveries shaping our understanding of the universe.

The Future: A Universe in Motion

With Rubin’s global survey underway, astronomy is entering its cinematic era. Soon, scientists won’t just take snapshots of the cosmos—they’ll watch galaxies evolve, clusters breathe, and stars dance in real time.

From static images to cosmic motion, we are witnessing the birth of a universal story told through data, light, and time.

— DatalytIQs Academy

You must be logged in to post a comment.