A new milestone in dark matter research reveals a mysterious, invisible object a million times heavier than our Sun.

In one of the most remarkable breakthroughs in modern astrophysics, an international team of astronomers has detected the lowest-mass dark object ever measured — using a sophisticated technique known as gravitational lensing.

This unseen cosmic mass, about one million times the mass of our Sun, lies roughly 10 billion light-years away, from a time when the universe was just 6.5 billion years old.

The discovery, published in Nature Astronomy by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, provides a critical piece of evidence about how dark matter is distributed across the universe — whether it is smooth or clumpy, and what that might reveal about its true nature.

Shedding Light on the Invisible

Dark matter makes up about 85% of all matter in the universe, yet it doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light — making it effectively invisible. Scientists can only infer its presence by observing how it bends and distorts light from background objects — a phenomenon predicted by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity and known as gravitational lensing.

“Since we can’t see these dark objects directly, we use very distant galaxies as a backlight to look for their gravitational imprints,”

explains Devon Powell, lead author of the study at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics.

Using this method, astronomers can detect dark objects that are otherwise completely undetectable by optical or infrared telescopes.

An Earth-Sized Telescope Network

The discovery relied on an extraordinary feat of global coordination.

The team combined data from multiple world-class instruments, including the Green Bank Telescope, the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), and the European Very Long Baseline Interferometric Network (EVN).

By synchronizing these telescopes across the globe, scientists effectively created an Earth-sized super-telescope, powerful enough to capture the minute distortions caused by the dark object’s gravitational pull on light from a distant radio galaxy.

The data were processed and correlated at the Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC in the Netherlands, producing images of unprecedented sensitivity and resolution.

A Hidden Mass Revealed

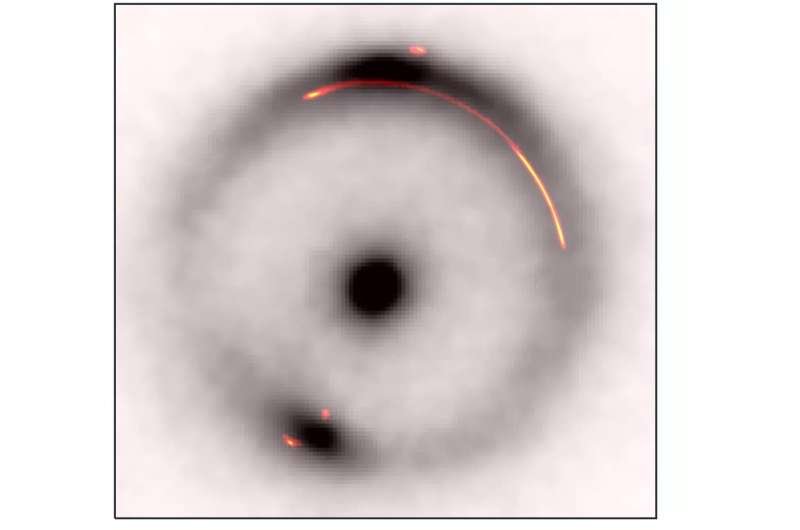

The key signature of the discovery was a “pinch” or narrowing in the observed radio arc of a distant galaxy — a telltale sign that something massive but invisible was warping spacetime in that region.

“From the first high-resolution image, we immediately saw a narrowing in the gravitational arc — the unmistakable sign of another mass between us and the galaxy,”

said John McKean, co-author from the University of Groningen, University of Pretoria, and the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory.

At the “pinch point” of the arc, sophisticated modeling revealed the presence of a dark clump — shown as a white blob in the team’s composite image.

Despite searches across optical, infrared, and radio wavelengths, no light emission was detected from the object, confirming that it is truly dark.

Cracking the Code of Cosmic Shadows

Detecting such a faint signal required supercomputer-level data processing. The team developed entirely new numerical algorithms capable of modeling billions of data points from the global telescope array.

“The data were so large and complex that we had to design new modeling approaches,”

said Simona Vegetti, senior researcher at Max Planck.

“Finding these dark clumps — and convincing the scientific community they’re real — takes an enormous amount of number-crunching.”

This dark object’s detection marks a 100-fold improvement in sensitivity compared to previous lensing studies. It provides the first direct evidence for low-mass dark clumps, consistent with predictions of the cold dark matter (CDM) theory — the leading model of cosmic structure formation.

Implications for the Universe

According to the CDM model, galaxies — including our own Milky Way — should be embedded within halos of dark matter filled with countless small “clumps” or “subhalos.”

Detecting these clumps is crucial because it allows scientists to test dark matter theories and distinguish between competing models, such as warm dark matter or self-interacting dark matter.

“Having found one, the next question is how many more are out there — and whether their abundance still agrees with theoretical models,”

said Powell.

If astronomers continue to find more of these invisible, starless objects, some long-standing dark matter hypotheses could be ruled out, potentially reshaping our understanding of cosmic evolution.

What Comes Next

The research team is now scanning other regions of the sky using the same gravitational imaging technique to look for additional dark clumps.

Each new detection will help refine how dark matter behaves at small scales — information vital for future missions like the James Webb Space Telescope, SKA (Square Kilometer Array), and LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna).

Their ultimate goal?

To build a 3D dark matter map of the universe — revealing the invisible skeleton that holds galaxies together.

Reference

Powell, D., Vegetti, S., McKean, J., Hämmerle, H., et al. (2025).

Detection of the Lowest-Mass Dark Object via Gravitational Lensing.

Published in Nature Astronomy (2025).

Credit: Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics / EVN / GBT / VLBA.

A Step Closer to Unmasking the Invisible Universe

This discovery doesn’t just push the limits of observational astronomy — it peels back another layer of the cosmic mystery that defines our existence.

Hidden in the dark, silent folds of space, these massive, unseen objects may hold the secrets of how the universe was built.

And now, with gravitational lensing as our cosmic flashlight, we are finally beginning to see the invisible architecture of the cosmos.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.