Background

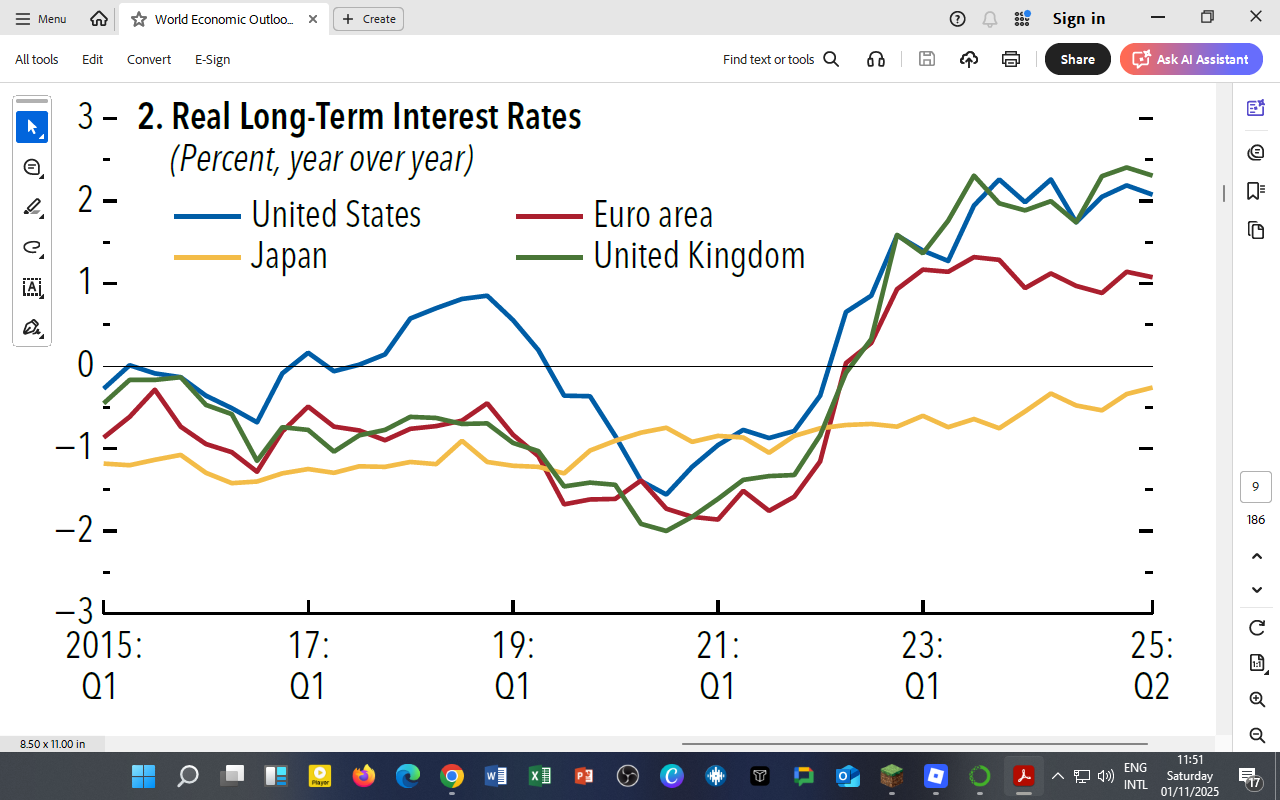

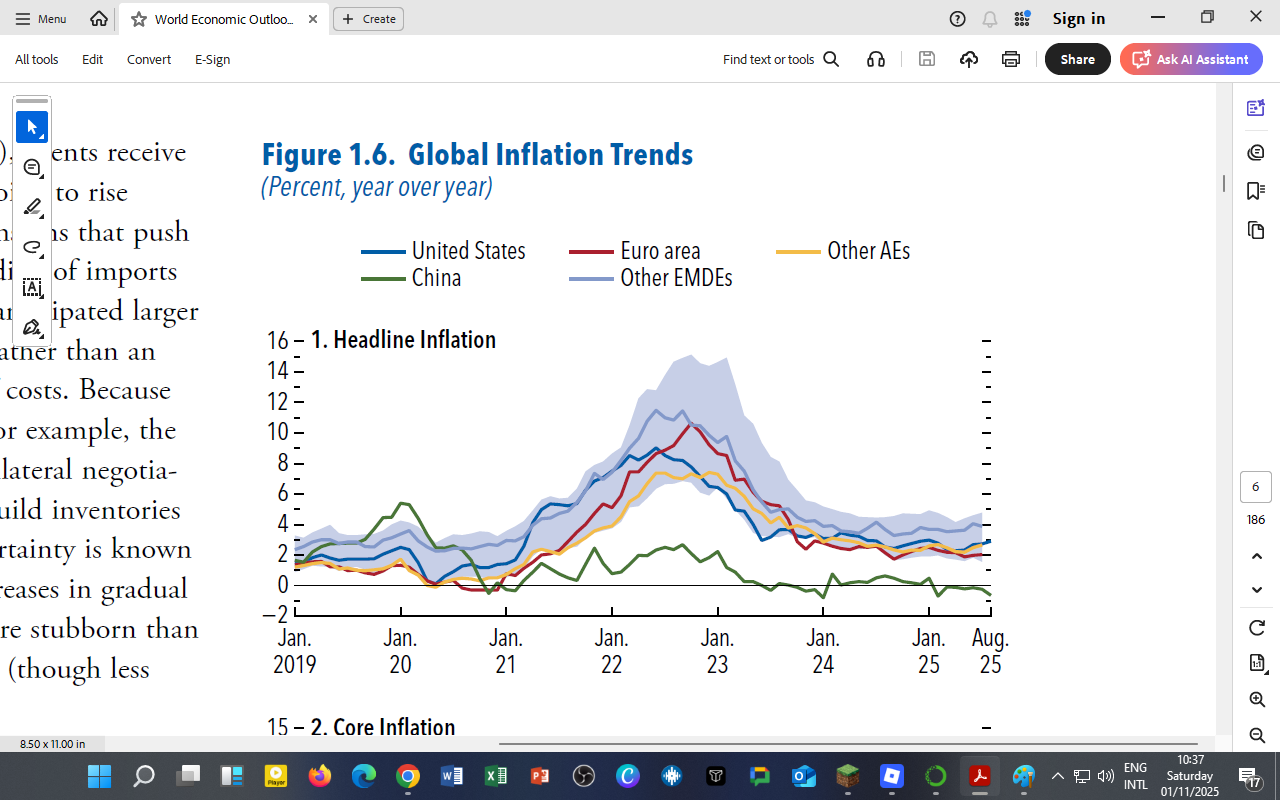

After more than a decade of ultra-low rates, the world’s major economies have entered a new interest-rate regime.

Between 2015 and 2021, most advanced economies saw negative real yields—that is, nominal interest rates minus inflation.

But by 2023–2025, the cycle turned: inflation cooled while nominal rates stayed high, producing the first sustained period of positive real returns since the 2008 crisis.

Figure — Real Long-Term Interest Rates (% YoY)

Lines represent:

-

United States (blue)

-

Euro Area (red)

-

United Kingdom (green)

-

Japan (gold)

Key Trends (2015 – 2025 Q2)

-

The Era of Negative Yields (2016 – 2021)

-

Inflation outpaced bond yields, pushing real rates below 0 %.

-

Japan remained persistently negative due to yield-curve control.

-

Euro Area and the UK followed similar paths amid accommodative monetary policy.

-

-

The Turning Point (2022 – 2023)

-

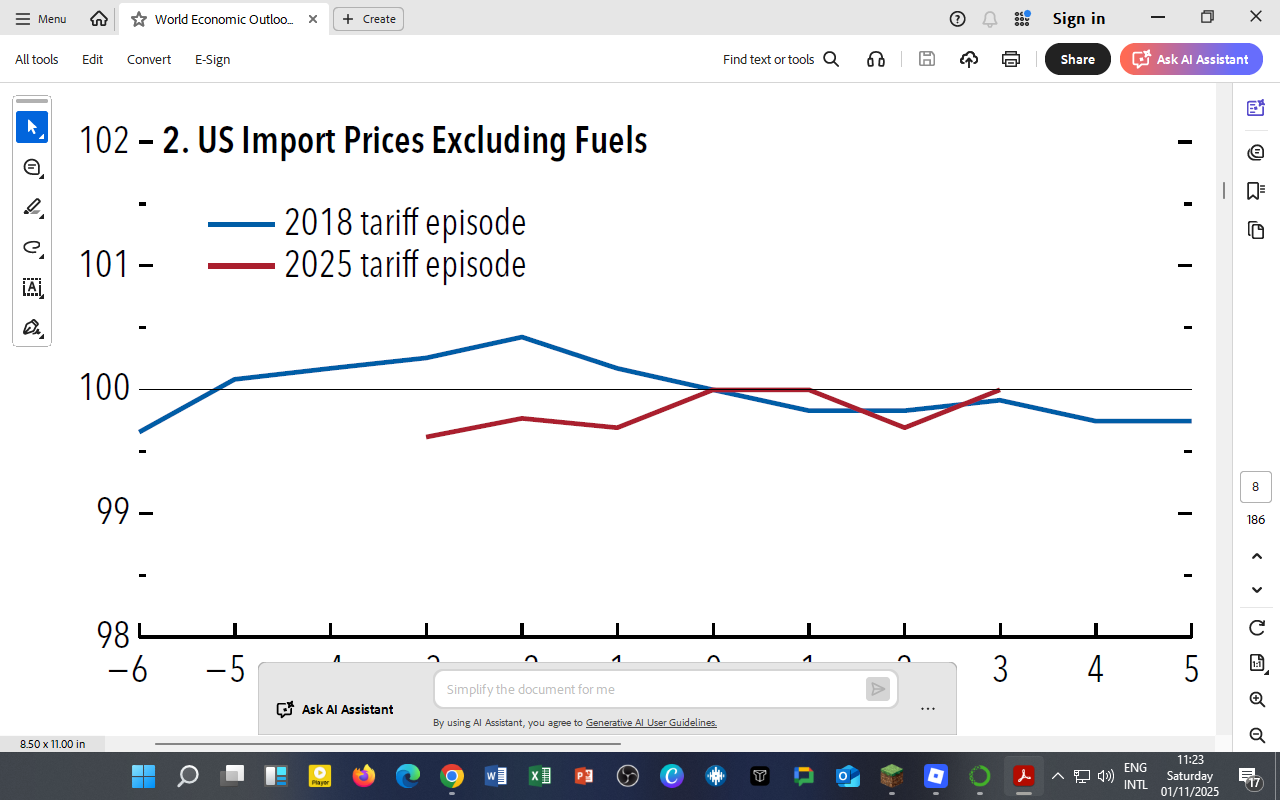

Inflation shocks forced central banks into their most aggressive tightening in decades.

-

The US Federal Reserve led the reversal, pushing real rates above +2 % by 2024.

-

The Bank of England and ECB followed, narrowing the gap with US yields.

-

-

2025 Stabilization

-

Real rates plateau around 2 % (US, UK) and 1 % (Euro Area).

-

Japan’s real rate remains near 0 %, reflecting continued deflationary expectations.

-

The world is adjusting to a “higher-for-longer” interest-rate environment. Investors are once again earning positive real returns, but governments face higher borrowing costs and slower growth.

Economic Implications

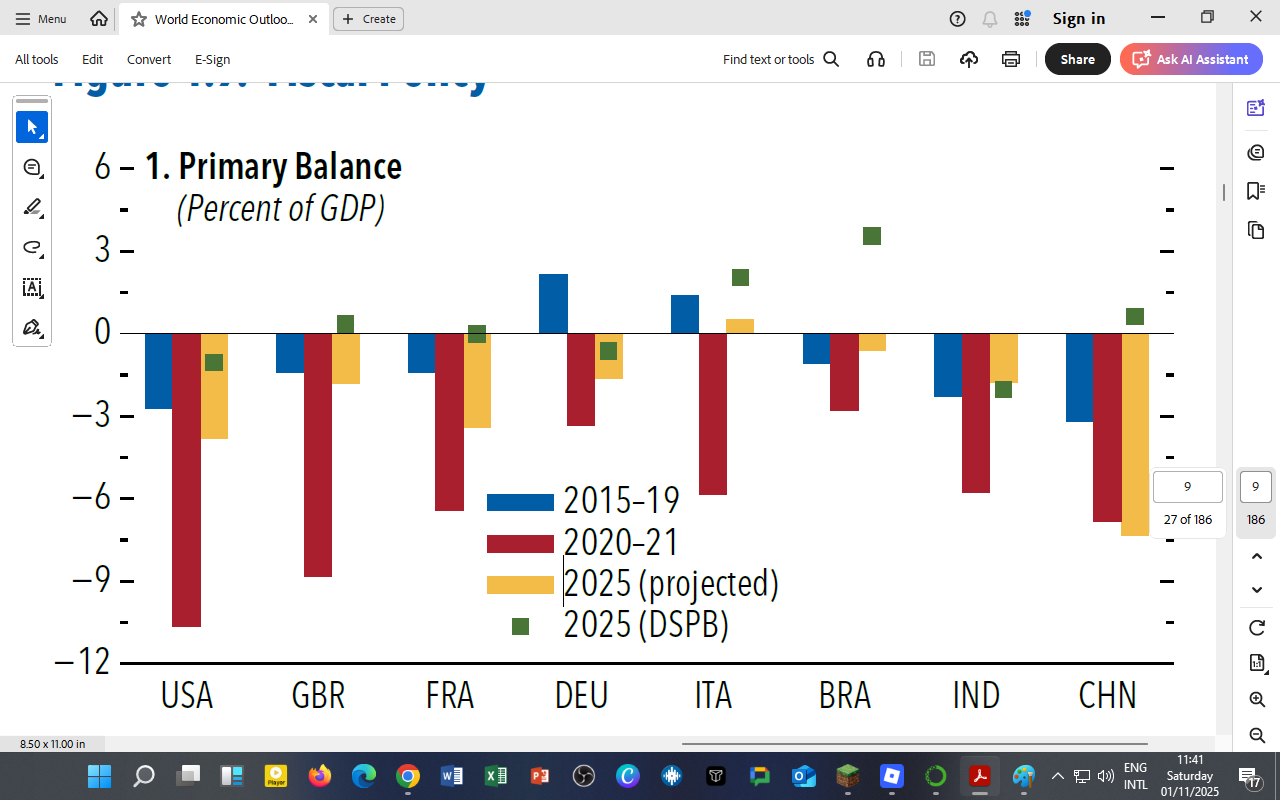

| Effect | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Pressure | Rising real yields increase debt-service costs for governments. | US, Italy |

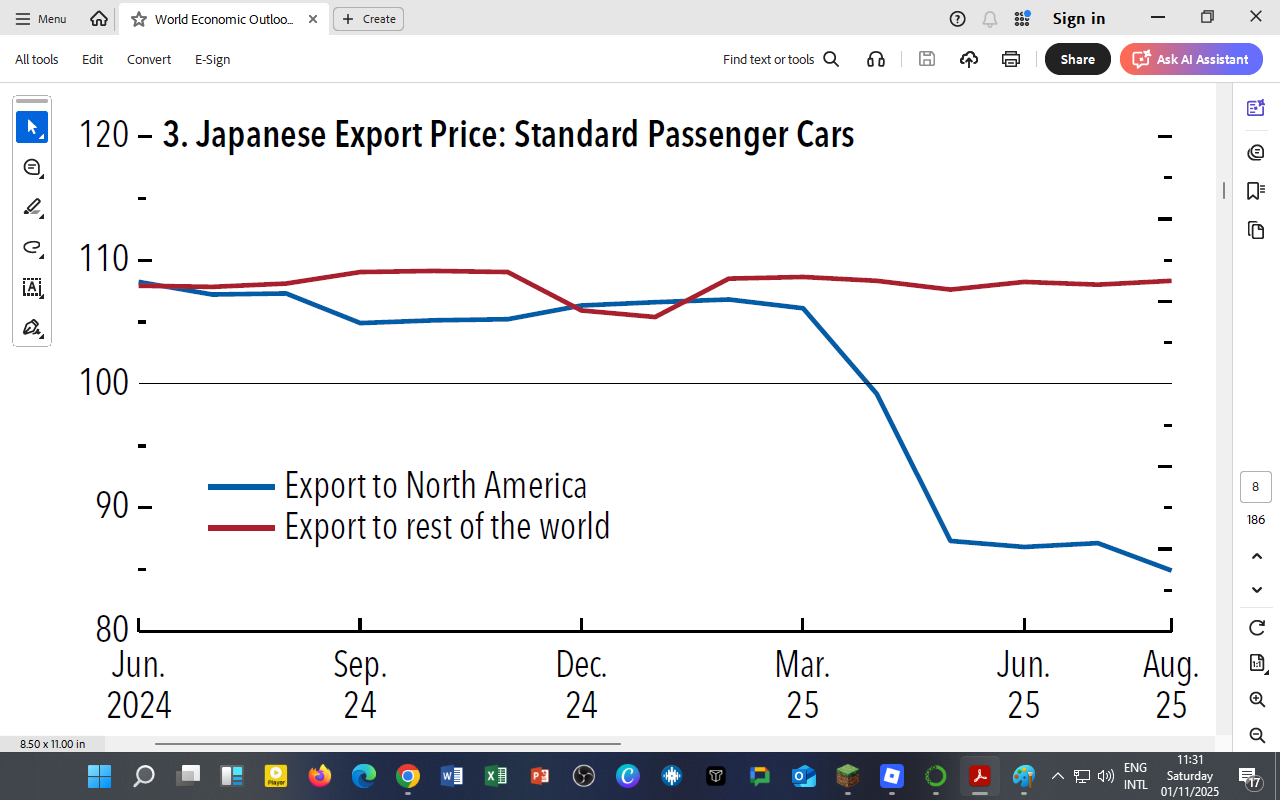

| Capital Flows | Higher US yields attract funds away from emerging markets. | Kenya, India |

| Exchange Rates | Dollar strengthens as real returns rise; yen and euro weaken. | USD/JPY > 160 in mid-2025 |

| Equity Valuations | Higher discount rates suppress stock-market multiples. | Nasdaq and FTSE indices adjust down 5-10 % |

Lessons for Kenya and Africa

-

Debt Refinancing Challenges: Kenya’s Eurobond re-pricing mirrors global real-rate increases. Higher yields mean limited fiscal room for infrastructure projects.

-

Investment Opportunity: Positive real yields globally signal a return to capital market discipline — Kenya can leverage its sovereign bond credibility to attract investors.

-

Policy Lesson: Stable inflation and fiscal transparency reduce risk premiums, allowing domestic rates to decline gradually.

Real interest rates link monetary policy and fiscal sustainability — when governments borrow heavily in a high-real-rate world, debt dynamics can deteriorate quickly unless growth accelerates.

For DatalytIQs Academy Learners

To extend this analysis:

-

Compute real interest rates = nominal bond yield − inflation rate (CPI).

-

Use Python’s

matplotlibto plot multi-country comparisons with custom legends and shaded policy periods. -

Explore Granger causality between real rates and exchange rate movements for Kenya vs the US.

Data and Acknowledgment

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook (October 2025) – Figure 1.10 (2) “Real Long-Term Interest Rates.”

Acknowledgment: IMF staff estimates based on Haver Analytics and national central bank data.

Author: Collins Odhiambo Owino, DatalytIQs Academy

You must be logged in to post a comment.