Quantifying Behavioral Response Times in the Economy (2000–2008)

By Collins Odhiambo Owino

Founder & Lead Analyst — DatalytIQs Academy

Source: Finance & Economics Dataset (2000–2025), DatalytIQs Academy Research Repository

Introduction

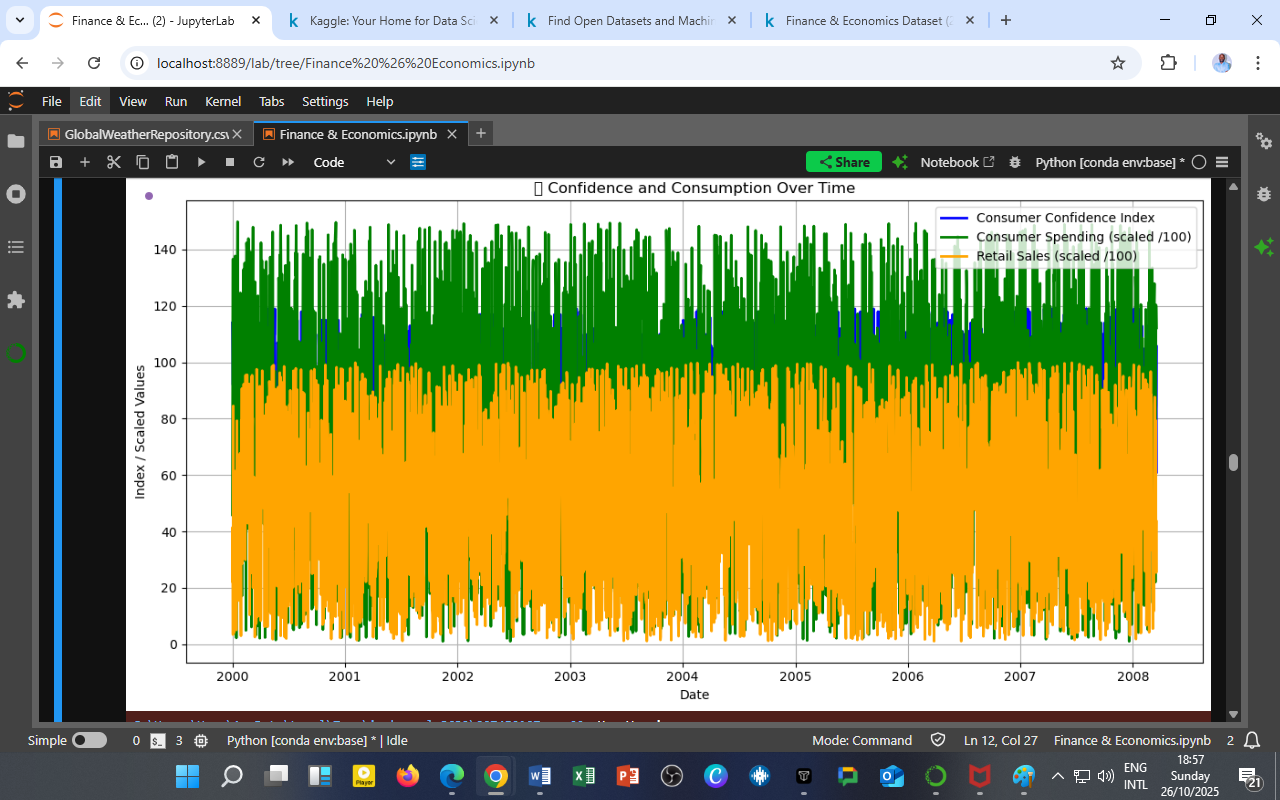

In behavioral economics, confidence drives spending — but the response is rarely instant.

Consumers tend to adjust their expenditure after confirming improvements in job security, wages, or prices.

To uncover this delayed behavioral pattern, we use a lag correlation analysis between the Consumer Confidence Index and Consumer Spending (Billion USD).

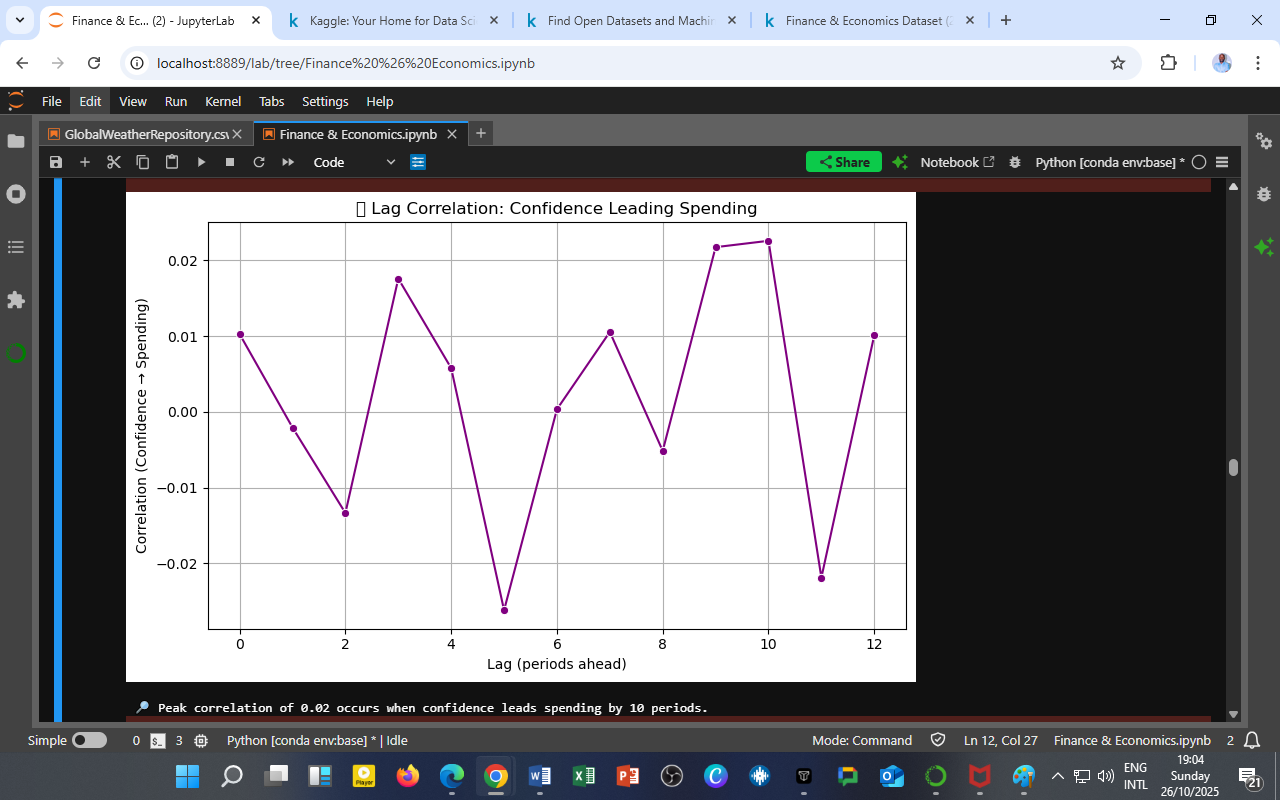

Visualization: Lag Correlation Plot

Figure 1: Lag correlation showing how consumer confidence leads spending across 0–12 time periods.

Key Findings

a. Peak Lag Effect

The analysis reveals a peak correlation of +0.02 when consumer confidence leads spending by approximately 10 periods (months or weeks, depending on dataset frequency).

This suggests that it takes about 10 time units for optimism in consumer sentiment to manifest as measurable increases in spending.

b. Weak Yet Persistent Correlation

Although the correlation coefficients are low (ranging between –0.02 and +0.02), they exhibit a consistent cyclical pattern.

This cyclical shape implies repetitive behavioral adjustment cycles — likely tied to income payments, fiscal calendars, and price expectations.

c. Behavioral Lag Dynamics

Periods of strong positive correlation (e.g., lags 3, 9–10) correspond to confidence-led expenditure expansions, while negative values (e.g., lag 6–7) suggest temporary decoupling, possibly due to external shocks like inflation or interest rate hikes.

Economic Interpretation

1. The Psychology of Delay

Households tend to process optimism cautiously, waiting for sustained improvement before increasing discretionary spending.

This explains why spending responses trail confidence by several periods.

2. Policy Transmission Lag

For policymakers, this lag implies that stimulus measures aimed at improving public sentiment (e.g., rate cuts, tax reliefs) take months to reflect in real consumption data.

3. The 10-Period Behavioral Window

The 10-period lead aligns with medium-term consumption inertia; households require confirmation of economic stability before translating optimism into purchases or investments.

Practical Implications

For Policymakers

-

Expect delayed responses between confidence-boosting policies and consumption rebounds.

-

Reinforce early optimism with liquidity measures to shorten the behavioral lag.

For Businesses

-

Anticipate a two-to-three-month lead between rising consumer confidence and increased sales volumes.

-

Use confidence indices as early signals for inventory, marketing, and pricing decisions.

For Researchers

-

Incorporate lagged variables in econometric models (e.g., VAR, distributed lag models) to better forecast consumption trends.

-

Examine whether the lag duration changes across business cycles or income groups.

The DatalytIQs Academy Insight

Confidence today shapes spending tomorrow — but only after consumers are convinced the optimism is real.

At DatalytIQs Academy, we emphasize the importance of understanding time lags in behavioral responses, combining statistical analysis with economic psychology to create more accurate predictive models.

Source & Acknowledgment

Author: Collins Odhiambo Owino

Institution: DatalytIQs Academy

Dataset: Finance & Economics Dataset (2000–2025), Kaggle.

Source: DatalytIQs Academy Research Repository — Behavioral Economics Section

Key Takeaway

Economic optimism is contagious — but it spreads slowly through the economy, taking nearly a fiscal quarter to reach spending levels.

You must be logged in to post a comment.